Inclusive education as a learning path

At the beginning of my teaching training, I mistakenly believed that, in highly diverse educational contexts, it was necessary to plan activities built around technology as that was the only way to ensure inclusion. However, my true learning came from understanding the steps that need to be taken even before planning a specific activity in order to create inclusive practices in the classroom where everyone is included.

Humility, respect and bi-directional learning

Working towards inclusive education must involve several essential elements such as the teacher's humility and unconditional respect towards the students. Each student is a unique individual with great potential and it’s important that teachers engage in prior personal work to help them learn to abandon judgment and labels. It is through this process that a respectful environment is created, initiating a connection with the students.

The teacher's humility is necessary to understand that learning is not unidirectional, this viewpoint represents a paradigm of the past that must shift towards a new scenario where the teacher acknowledges and values the power of bidirectional teacher-student learning. In this wonderful profession the more you discover, the more gaps in your own learning become clear — as teachers we learn so much from every interaction with our students. True inclusion stems from the learning that each student offers us on a day-to-day basis.

What role does “planning” play in inclusive education?

An inclusive classroom requires planning a space where all individual needs are met (all of them, with no exception). When I had just started teaching I thought it was unrealistic to try and reach 100% of my students’ needs in any single same session, influenced by my own limiting beliefs and educational tradition and the rigid ways of working present in the educational system in which I was raised. Nowadays, after various experiences working on inclusion, I am sure that this is not impossible; it simply requires effort to involve all stakeholders in the process, especially our students. Each student has different needs, so the planned classroom activity must encompass them all through various modalities within the same overarching activity.

Example of inclusive education practice in the classroom

In my case, successful inclusive activities in the classroom have resulted from collective work. Extended conversations within the school team, implementing active listening with them, and building a connection with the students have been crucial. One such example was an activity my co-teacher and I proposed focused on understanding climates in different regions of the world.

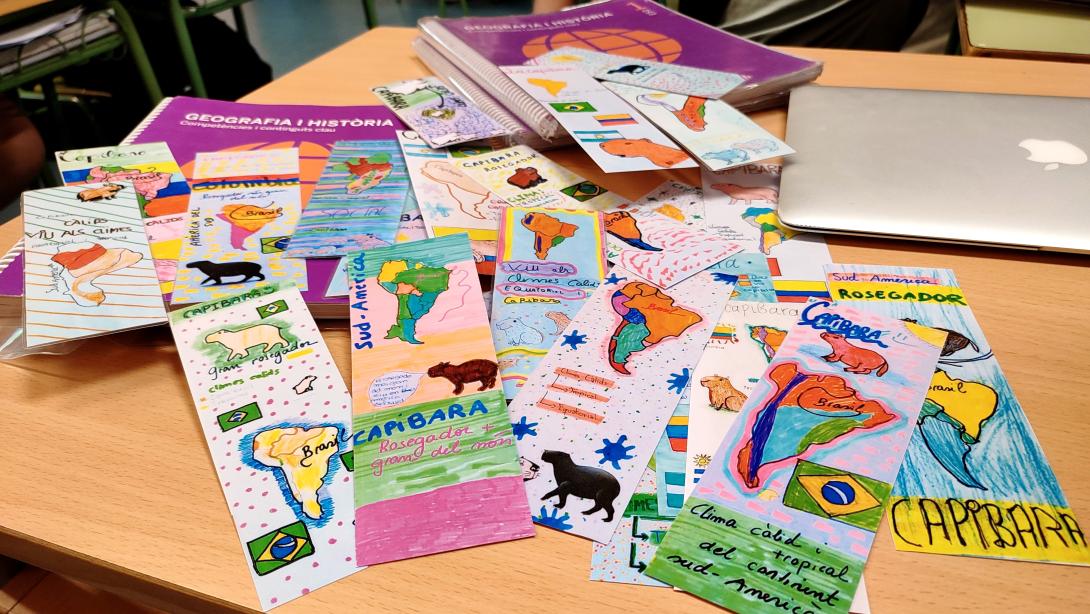

We asked our 13-year-old students to choose an animal from each world region that was relatively unfamiliar in our daily context. For example, for South America, they identified the capybara. To help us achieve consensus on the animal for each region we were drawing on and reinforcing skills such as active listening and empathy that we had worked on with them before this activity. It is worth noting that this was a very diverse group in terms of ethnicity, language, religion, and national origin: around 70% of the school came from families who had emigrated to Spain from Algeria, Colombia, Ghana, Gambia, Morocco, Peru, Senegal, and Venezuela. The class thus consisted of students born in Spain to migrant families, as well as students who had themselves migrated, representing around eight nationalities. Regarding educational backgrounds, it was observed that there were varied educational levels; although the students were the same age, their experiences in the education system differed significantly.

Once the animal was identified, an A4 paper was divided into two equal parts through a longitudinal line along the entire vertical center of the sheet, with each student having one of the cutouts. The activity involved drawing, in that space, a map of the continent, in this case the Americas, specifying the regions where the capybara lives, and indicating the different climates from Canada to the Argentine and Chilean Patagonia.

The activity was adapted for everyone; for example, in the case of a person with reduced visibility, a relief map of the American continent could be provided (created through the educational center's 3D printer). Instead of drawing the map on paper, they would create it in the same space as their classmates, using clay or a similar material with textures.

After creating the maps, colored and with some words indicating climatic characteristics, a high-resolution photo was taken of each one made by the students. Once digitized, they were printed as bookmarks (5cm x 20 cm), and they could also be printed with a certain relief. The students gave the final presentation on the activity, and at the end of the exercise, they were able to identify the different climates of the American continent and have a clear understanding of the regions where, for example, the capybara lives or does not live.

A supportive network of peers

The idea for this classroom activity came from a South African friend of mine, Gabrielle, whom I met years ago while I was working in Cape Town. This exemplifies the power of collaboration and sharing best practices, demonstrating how valuable it is to have a network for exchanging ideas and improving our approaches. In fact, the key tool linked to networking among education professionals is having a support network, regardless of distance, with whom to share classroom proposals. This point, for me, is one of the most powerful and took me the longest to understand.

Having connections to colleagues like Almudena, Aaron or Marina, and many others, whom I met during my fellowship program with Empieza Por Educar, and who are great teachers working at the other end of Spain from where I am, or Loreto, a Chilean friend from Santiago de Chile whom I met during my second-year summer professional placement in the program, can significantly enhance your teaching practice. Loreto's 30 years of experience teaching in high-vulnerability schools has provided me with new approaches and insights that help me connect with my students in ways I wasn't previously aware of.

I am truly grateful for the power of collaboration and the generosity of sharing best practices, not only from colleagues but also from the entire excellent team of professionals at Empieza Por Educar and the broader Teach For All network. Their support has been invaluable in advancing my work in inclusive education as a learning path. Even after the program ends, they remain friends who are there for anything you might need. It is genuinely inspiring and, above all, very human.