The case for inclusive deaf education

The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 4 emphasizes inclusive and equitable education for all, but many learners with specific learning needs are still kept at the periphery in the realms of learning. Teach For All’s Inclusive Education Fellowship is an important initiative to help melt the boundaries of exclusion due to many factors, specifically focusing on learning differences and disabilities. The goal of inclusive education is to provide equitable education opportunities for all learners, including those with specific learning needs.

In this piece, I want to focus specifically on the issues pertaining to inclusive deaf education and the inclusion of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing (DHH) in mainstream educational institutions. Through Teach For Uganda, I started my journey in the classroom as a teacher of English language and literature. Later, I was also part of a delegation from Uganda Martyrs University (UMU) that attended a training about the possibility of creating a deaf inclusive teaching-learning environment conducted by the experts from the Netherlands courtesy of Kentalis International Foundation. Subsequently, a Bachelor of Inclusive Deaf Education (BIDE) program at UMU was developed and accredited by the Uganda National Council for Higher Education (NCHE) and then launched in 2019. I currently teach three different courses on the BIDE program.

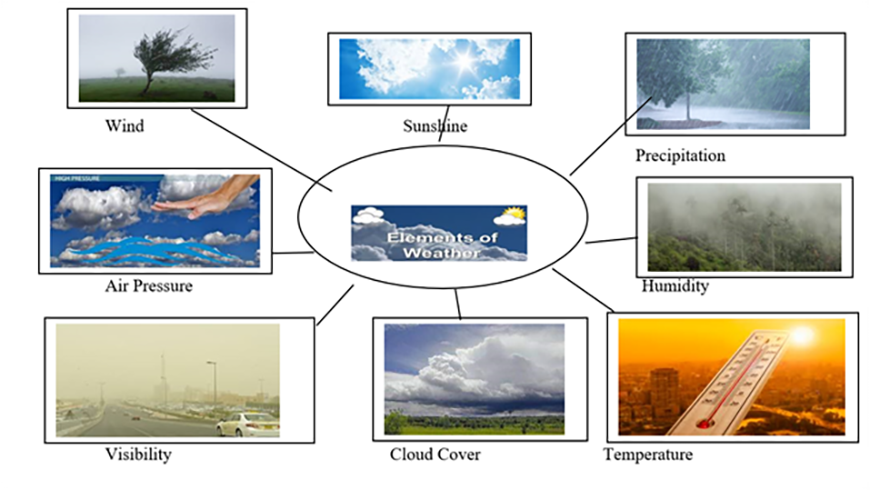

The DHH have auditory challenges but compensate for this largely through their sense of sight, implying that during teaching-learning, course instructors need to appeal to DHH learners’ sense of sight as much as possible through visual aids such as pictures/images, diagrams, graphs, captions, and/or notes sharing. Visualization presents abstract concepts and ideas in a concrete form that renders such concepts more comprehensible to the DHH, as well as to all those in a classroom who may prefer to digest information visually. For example, the visualization below demonstrates how a teacher could break down the elements of weather to help students understand what the word “weather” means. Research has found that visual information is perceived faster and more directly as evidenced by the trend toward the mass use of infographics and data visualization in classrooms around the world. Additionally, the use of captions on videos and sharing of notes helps in bridging the communication gap between the hearing and the DHH as it provides a platform for subsequent reference, thus reinforcing understanding of the study material in question regardless of the difference in hearing.

According to Mike Oliver’s social model of disability, learners with specific learning needs only require an enabling environment to compete favorably. The social model of disability aims at diverting attention from functional limitations of individuals with a disability, to the challenges caused by the disabling environment, barriers, and cultures. In this way, it’s important to consider the ways traditional educational environments do not serve learners with specific learning needs in order to develop solutions for more inclusive education. For example, I know people who were born deaf and were not served by traditional education but who, through supervised informal training, were able to learn skills like construction and eventually passed national examinations under the Directorate of Industrial Training program that was established by the Ministry of Education and Sports to equip and promote employable skills in persons without formal education but with examinable skills.

In advocating for inclusive education, all educators should ensure that learners with specific learning needs embrace studying in mainstream institutions of learning not as a moral obligation by stake-holders, but as an empowering choice to help better prepare such learners to cope with possible opportunities and challenges they may face in the society beyond schools or education centers. Furthermore, the best practices that teachers and schools employ and that we reflected on in the Inclusive Education Fellowship, like Universal Design for Learning, Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy, and Metacognition are known to enable more progress for all learners.

Ultimately, if we want to transform education to cater to and promote inclusivity, it’s imperative that all stakeholders actively and committedly participate in creating inclusive learning environments. Ensuring inclusion of all learners must start with policies to promote inclusivity in mainstream schools and equip educators with required skills. For example, to work more inclusively with DHH learners, teachers would benefit from: training in inclusive teaching didactics, sign language proficiency, and gaining deeper knowledge and understanding of deaf culture. The campaign towards inclusivity in education is not at zero, though there is still a long way to go, and educators need to continue to advocate for inclusion more broadly as well as working to promote inclusion in their own classrooms.