Leading From Lived Experience: Healing the Wounds of History in Medellin

The Leading From Lived Experience fellowship brought together over 30 staff members, alumni, and participants from partner organizations in 15 countries across the Teach For All network, who have all personally experienced various forms of inequity, marginalization, and discrimination in their own contexts. The fellowship’s aim is to explore how its members can draw on their lived experience to collectively build power, heal, resist, and create change locally and globally.

The fellowship chose Medellin, Colombia as a place to come together because it is a city that is in the middle of an incredibly difficult and yet inspiring journey of healing and transformation, driven by community-rooted collectives dedicated to reimagining a different future by honoring both the pain and richness of their past.

However, Medellin is a city still fighting to break free from narrow narratives that have often been imposed from outside—and sometimes from within, too. One of the stories the global media likes to tell focuses only on drug trafficking, violence, crime, corruption, and war. And while it is true that all of these factors have shaped the city’s past and present—still today, many young people living in marginalized communities endure routine violence and struggle to survive stark inequality and poverty while caught in the middle of conflicts between powerful interests beyond their control—this narrative alone does not acknowledge the incredible energy, resilience, and creativity of the members of Medellin’s communities who are working to shape a different path forward.

There is also another single story told about Medellin, the “Medellin miracle,” in which progressive government action is credited for turning what was once known as the most dangerous city on Earth into “the city of innovation.” And while local government investment and innovation in infrastructure, education, and culture (often designed in partnership with community leaders) have had significant impact towards equity, expanding access, and opportunity, this narrative is often used to gloss over historic and enduring forms of systemic injustice and deep-rooted social inequalities, and at the same time erase or tokenize the contribution of the community collectives that continue to be a driving force behind the city’s progress.

In Medellin, the group spent time with some of the community collectives across the city that are working to reclaim and reimagine their own stories and who, in honor of their lost ones, are crafting new narratives and realities grounded in truth, hope, culture, creativity, healing, and resistance.

The following is a reflection by Teach For Uganda Fellow Charles Obore on his visit with the Agroarte collective:

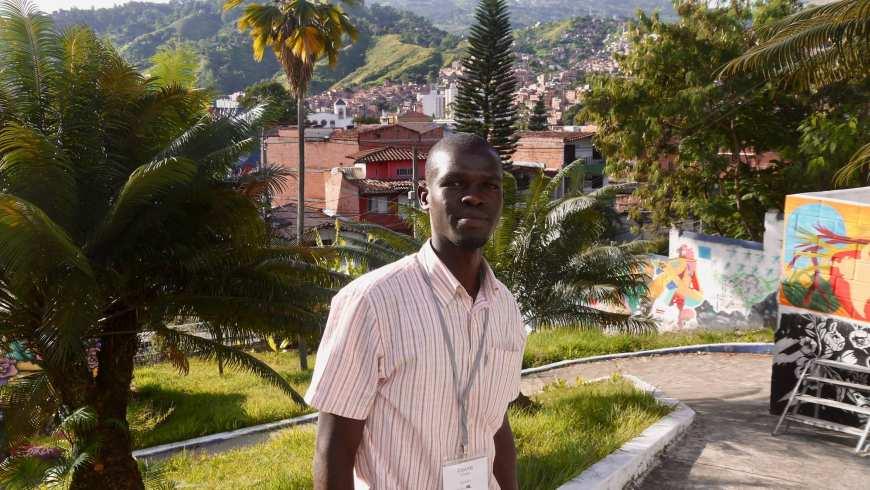

Charles, second from left, with other Leading From Lived Experience Fellowship participants, in Comuna 13 (Photo by Faolan Jones)

Narratives can be changed for the better when people come together as a community, united by their history, culture, and what they love most.

Teach For All’s Leading From Lived Experience Fellowship offered the opportunity for 30 representatives of the network, from 15 different countries all over the world, to visit Medellin, to experience the city from the perspective of those who live there, and learn how these communities are trying to heal their wounds and create a better future.

Medellin welcomes you to her heart with sky rocketing buildings and magnificent small structures constructed on top of each other up to the peak of a mountain. When your eyes come into focus on the captivating terrain of the city’s mountainous landscape, it can take your breath away.

The entire skyline of Medellin is avalanched with fauna that make the city look like an earthly paradise. The elegant murals all over the city walls are not only stunning but also keep you abreast of the Colombian culture and history. This, in addition to the rightful dose of Medellin’s hip-hop and Afro beat music, almost inspired me to look into Colombia’s immigration policies. Who wouldn’t wish to live in what might be the world’s most innovative city?

To dig into the philosophy of Medellin, we had to visit its local communities. A 30-minute ride from the city’s centre, taller buildings diminished as a clear view of the indigenous Medellin began to surface.

On arrival at Comuna 13, once one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in the city, we were welcomed by a community leader known as El AKA from the Agroarte collective, who offered us a free lecture on the local hip-hop style of greeting before leading us to Casa Morada, a small apartment full of pictures and writings in Spanish. Amidst the writings, you couldn’t miss the musical instruments. Young people were seated in different groups, each seemingly in deep reflection. We were later told of the various community planning meetings that were going on. With great hospitality and a heartwarming smile, Aka offered us each a glass of water. With long dreadlocks, big Afro trousers, and looking to be in his thirties, he picked up a marker, rolled over a white board, and took us through the history of oppression and resistance in Comuna 13, Medellin and Colombia at large.

Photo by Charles Obore

He shared his analysis, explaining how the country's long civil war was used to maintain and strengthen the monopolization of land and resources by a handful of powerful families, while the chaos and desperation of the conflict created the conditions for the drug trafficking trade to take deep roots in the city. At one point the government, paramilitaries, guerillas and cartels were all waging warfare in the narrow streets of his community, with military helicopters firing indiscriminately into crowded homes. And although the war is officially over the violence continues.

"Thousands of young people have died and still hundreds continue to die,” he told us. “We have lost over 400 community leaders [across Colombia by assassination] just in this year alone. Even me personally, as a leader of this community, I fear for my life.”

Caught in the middle of conflicts between rival gangs, powerful private interests and the military occupation of his community, standing up as a leader for the good of people means risking life and death. This incredible young and optimistic leader does not live with his family and constantly changes homes for fear of his life. His unflinching resolution to lead his community to a better future is remarkable.

"We know we have a bad history and some of those crimes are still going on, but as a community we can't let that define our future and that of our children,” he explained. “We shall keep those memories of our history and culture alive as we heal the wounds. It's that history that directs us and informs our decisions.”

The many murals and paintings in the city of Medellin are not for decoration. Each represents and reminds its residents of their culture and history: the heroes who died defending their communities, women who were killed in search of their children, leaders and artists who were murdered in the pursuit of freedom for their people. You don't need to buy a book to understand Medellin’s history, you just need to walk the city’s streets.

Photo by Faolan Jones

As we walked around the community, we found groups of women gathered to water plants. When we asked them the source of their motivation, one of them said, “Almost all of these trees you see in this area were planted by the community, especially by the women.”

“For Every person who dies in our community,” she added, “we plant a tree as a way of remembering and keeping the spirit alive.” As she spoke, I remembered how we do this in my own country, Uganda, where instead of planting we cut the trees to gather firewood for cooking at the funerals.

We learned that the groups of women we encountered had gathered to water plants in reminiscence of the 345 sons who were ‘disappeared’ when the war landed on their community in 2012 claiming thousands of lives, and in protest of the government that refused to formally acknowledge and investigate their deaths. “Visitors, you must also leave your memories with us by planting a tree," the woman politely instructed us—which left me thinking aloud, How can people be taught to love nature this much?

Back in the office of Casa Morada, we visited a nicely decorated room that was well equipped with all kinds of musical instruments. The most outstanding was the local African drum, one of the most popular instruments played by the Afro-Colombians. Young people gather in this room at any time of the day, but mostly in the evenings to socialize and, most importantly, to learn how to sing and play the type of music intended to heal wounds, conserve the culture, and inspire unity, peace, and prosperity among the community.

Alongside representatives of 15 countries all over the world who were brought together by our shared connection to the lived experience of the children and communities we work with, I had come to drink from the cup of oppression and resistance of Medellin. After all that I had seen and heard, I found myself compelled to ask the question: What will Africa, my motherland, learn from this memorable experience?

Firstly, Africa needs to recognize that its dignity and indigenousness are present in many continents and countries, including Colombia, where Afro-Colombians alongside Indigenous peoples native to Colombia, have historically endured slavery and segregation, and continue to resist ongoing discrimination and marginalization.

Secondly, Africa has to derive its own cultural mechanisms of writing, documenting, and being proud of her history. Unfortunately, our very rich history is often told by foreigners, who use our stories to benefit their own interests. Our culture must not be overtaken by western civilization; we must protect and preserve it dearly.

Thirdly, war can never be the first option for solving our political, social, and economic challenges, as it actually cripples us even more. Africa cannot choose to be at war with herself. We need to revise our history, create mechanisms for healing our people from old wounds, and inspire them to live and work together, and pursue our collective goals with inclusivity. We have to recognize that our culture, social life, music, men, women, and children can all play a role in this process of healing.

Fourthly, no government can ever solve all of our problems. Medellin’s challenges have not been addressed by the government alone. Its communities have recognized their power and the role they have to play to solve those challenges. Africa needs to start mobilizing grass roots, community-led initiatives inspired by a collective vision. Surrendering our hopes to politicians for so long has destroyed our efforts to prosper as a continent.

Lastly, we must recognize and appreciate the global world we are living in. We should embrace entities and organizations like Teach For All that have chosen to open doors for global connectivity, so we can learn from those who have faced histories like ours and are working to overcome the trauma. As we learn from them we must borrow only what's relevant and appropriate to the context of our communities, and not destroy, dilute, or kill our culture and history at the expense of modernisation and economic prosperity.

I’m grateful for the opportunity to learn from the people of Medellin, Colombia, and the many new friends from all over the world participating in the Leading From Lived Experience Fellowship. Together in this remarkable city, we shared an unforgettable experience of learning, unlearning, and relearning.

Photo by Carlo Fernando