The Ripple Effect: Equipping girls to navigate crises, assert their rights, and challenge harmful social norms

Lee esta historia en español

With the theme, The girl I am, the change I lead: Girls on the frontlines of crisis, International Day of the Girl 2025 is an opportunity to highlight the leadership of female educators and students who are teaching, learning, and creating positive change in crisis contexts. In the following reflection, Enseña por México alumna Wendy Gallegos shares her experience teaching in a community where violence and sexual harassment are common, and how her perspective on leadership was shaped by witnessing how girls living in contexts of crisis and violence can still find ways to lead change and transform their realities.

From 2021 to 2023 I served as an Enseña por México fellow in the state of Guanajuato, one of the regions with the highest levels of violence in the country, including some of the most dangerous cities in Mexico. This context affects girls in particular: in Guanajuato, more than 60% of women have experienced some form of violence in their lifetime, and girls and adolescents are especially vulnerable to sexual violence and school bullying—situations that often limit their ability to dream, act, and lead change in their communities.

Throughout my professional journey, life has placed me in different roles and contexts—each with its own unique value and important lessons. However, working with middle school students also led me to question what we, as a society, are doing to stop harming children and young people, particularly girls who are growing up in environments marked by violence.

During my fellowship in Chichimequillas, a community in Silao, Guanajuato, I witnessed how the community faced serious security challenges driven by two main factors: first, parents being absent because they had migrated, and second, individuals engaging in criminal activities such as armed robbery or drug trafficking. These circumstances turned the community into an unsafe place not only for outsiders but also for locals—to the point that children were told to stay indoors when they returned from school.

As a fellow in that community, I encountered a reality that left me feeling powerless and disheartened. My students, though full of energy, creativity, dreams, and goals, were also profoundly alone. They had no one they could truly trust. Many carried stories of abuse within their families, and fear was always present: fear of violence, fear of the narco (members of a drug cartel or gang), and above all, fear of “not becoming someone”—as they themselves put it.

As I watched them grow, I noticed how they began to learn to relate to one another through gender roles and stereotypes. I saw how they accepted, with discomfort, the touching and sexualization of their bodies—how boys were allowed to harass and bully girls “because they were men,” how girls were constantly competing to humiliate one another and show off the “best body.” Conversations about other people’s bodies were filled with mockery and disdain. Teachers and administrators knew about this, but dismissed it, arguing that girls were just “too clever and mischievous,” and that boys couldn’t help it—that it was simply their nature.

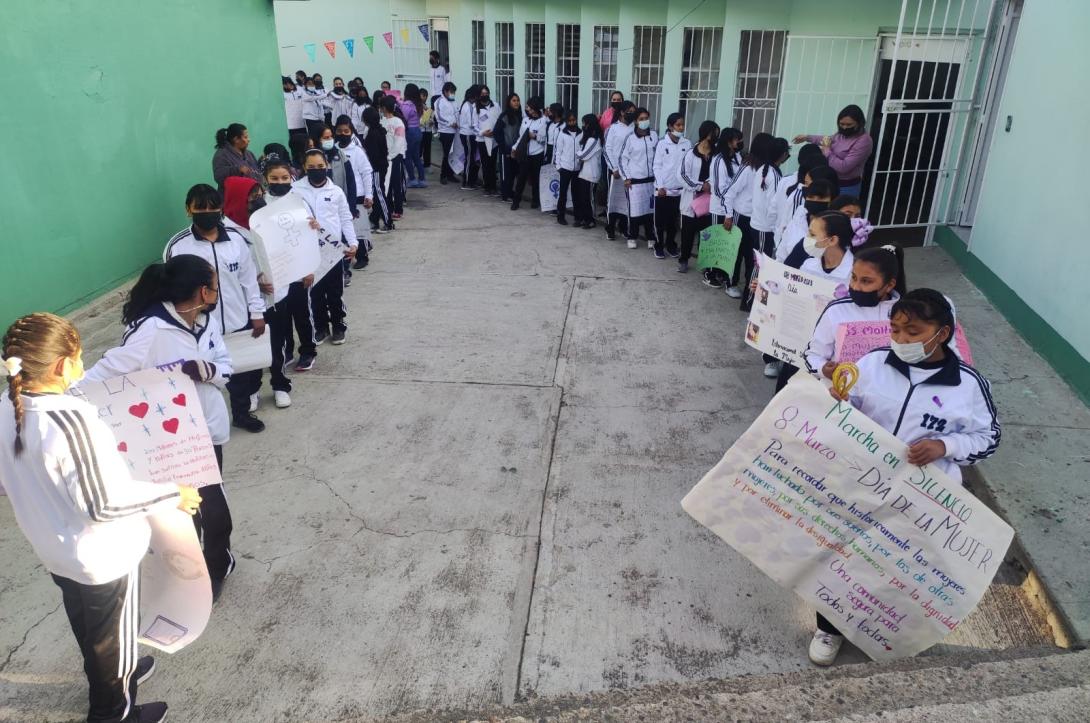

When I decided to take action, I began working with the girls. Together we explored sisterhood and the power each of them had to make decisions about their own bodies. They had never spoken about these topics before, but they immediately connected. Even those who had been “rivals” took time to listen and share. In those moments, they worked together and advised each other on what to do and who to turn to if they ever needed help. They told me they wanted to organize a march like the ones they saw on TV to protest violence against women, especially since March 8, International Women’s Day, was approaching. After a long debate with the school administration and with the support of some teachers, permission was granted. It was a battle won that filled them with hope.

There was also work to be done with the boys. With the support of my leadership coordinator, we designed a school-wide workshop on harassment prevention. We analyzed popular songs and videos that normalized gender and sexual violence, questioned the games they played with each other, talked about harassment, reviewed the violentómetro (a tool to identify levels of violence), and, finally, discussed consent. It was moving to see their surprised faces as they asked: “So, does that mean I harass?” “Now what do I do?” “How do I tell my mom there’s violence at home?” “Then how are we supposed to tell girls they’re pretty?” Together, they figured out how to reshape their ways of relating to one another.

Change did not happen overnight, and I cannot even say I saw it fully unfold. But I was left with the certainty that something shifted. The students learned that there were other possibilities. I still hold on to the memory of their mischievous, uncertain faces as they hesitated, not knowing if they were crossing a line—but the very fact that they stopped to think about it showed me that the effort had been worth it.

This experience highlights how initiatives like these, even at a local school level, equip girls to navigate crises, assert their rights, and challenge harmful social norms. When girls are supported to act as leaders in their communities, it creates a ripple effect that can help address broader systemic issues, such as widespread violence and gender inequality, demonstrating the critical importance of empowering girls on the frontlines of crisis.