Staying Connected: Teach For Pakistan Fellows Respond to the Needs of Their Students Despite the Distance

When the COVID-19 pandemic shut down schools in Pakistan, Rabiah Chaudhry was teaching social studies to fourth graders at a government school in Nurpur Shahan, Islamabad as a Teach For Pakistan Fellow. While a national school closure wasn’t something they’d ever even imagined having to deal with, for Rabiah and the other Teach For Pakistan Fellows, “inaction was not an option.” The Fellows knew that their students were already at a greater risk of dropping out and realized that maintaining contact with their students was critical to continuing to meet their needs even when they were physically separated. Their initial focus was on reaching out to their students to find out what they needed so that they could build their strategy in response to these needs.

The Fellows asked questions to understand the specific circumstances of each of their students. They used this information to assess the best way to remain connected to them and support their learning - Did they have a phone, or a TV or radio? Did they have internet connectivity? They also sought to understand who the members of their students’ households were and who among them might have enough literacy to help the students.

Immediately, they realized that the most urgent need for students and their families was access to basic rations. So the Fellows’ next effort involved connecting families in need of food and supplies with the services and organizations providing these. For some communities, they even created their own fundraisers and purchased rations themselves.

The Fellows recognized that their students’ needs were psychological as well as physiological. “Our kids were going through a really tough time in which they’d lost the safety of their school,” Rabiah explained. “They had lost all of their connections with their teachers, with other students, and they had lost all structure and routine and were in a place of uncertainty where they were worried about everything.”

|

Image

Image

|

|

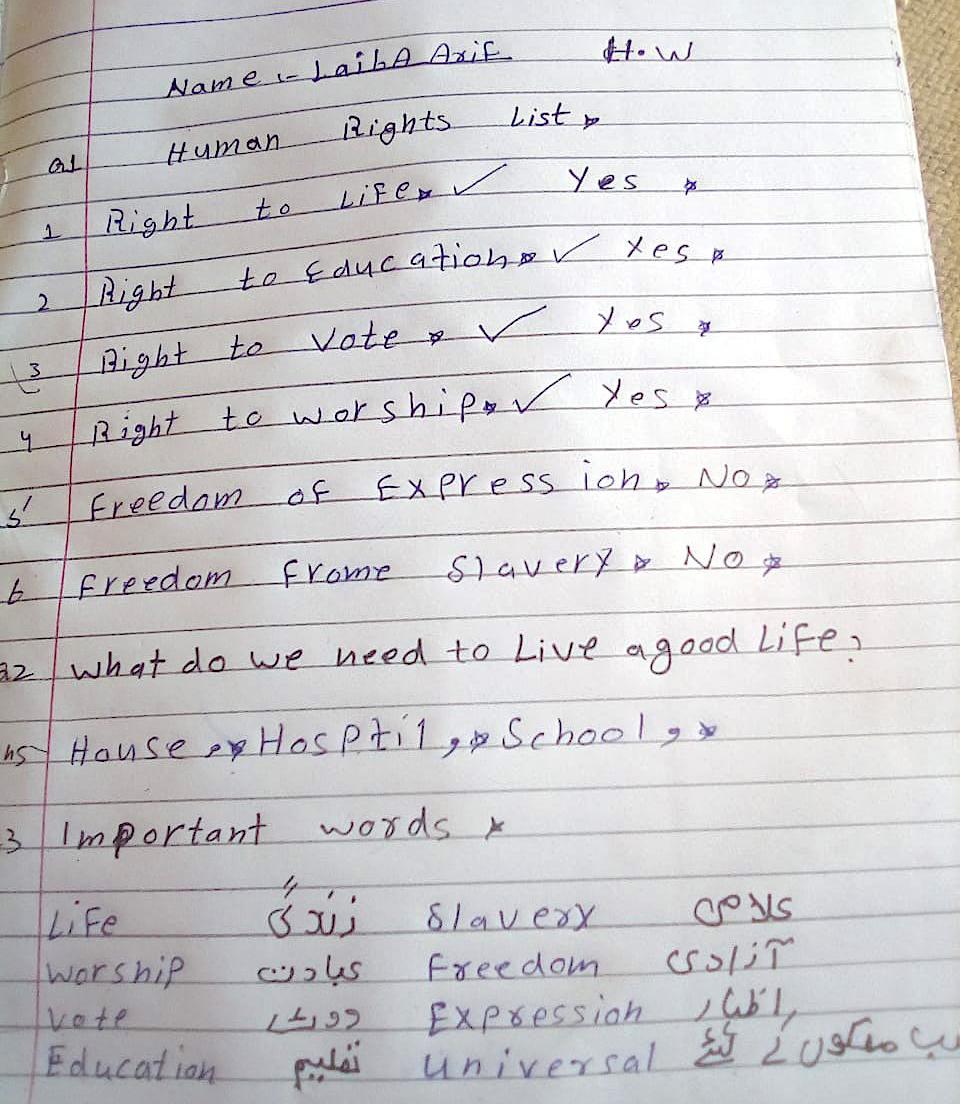

One of Rabiah's students' response to a social studies |

With this in mind, when the Fellows started to plan their lessons, the first thing they focused on was developing content to help their students’ wellbeing and mental health. They asked themselves, how can we help our students understand what’s happening and process it? How can we keep them physically active? How can we keep them connected to each other and the broader community? They also brought this mindset to the academic content they developed and tailored it to the current situation. For example, in her social studies lessons, Rabiah discussed her students' civic duties during the pandemic, and explained economic concepts in relation to the lockdown. Similarly, Fellows who teach English focused on building their students' vocabulary with terms that would help them understand the news and reporting around COVID-19.

The content was designed keeping in mind that its delivery and engagement would need to be differentiated according to the kind of technology students could access. This was where the Fellows’ initial research to understand students' individual circumstances really paid off. They found that they were able to partner deeply with parents who, even after losing jobs and income as a result of the lockdown, were determined to do whatever was necessary to ensure their children continued their education. For some, this meant buying internet enabled phones, while others coordinated with family members to share devices, and one father even found an office outside of which he could access free WiFi and traveled to it every day in order to download content and bring it back home to his child. “There’s so much that the parents were prepared to do,” Rabiah shared.

The Teach For Pakistan Fellows found that their students fell into two groups – those who had access to WhatsApp, and those who only had access to SMS. With this in mind, they created PDFs, voice messages, and notes they could send via WhatsApp to the first group and, since they were only able to share some information over SMS with the second group, they made sure to supplement it with printed learning packets. The packets are distributed to focal people in the communities from whom students can retrieve them. The Fellows have also paired students from both groups in a buddy system so that those who have access to the additional content through WhatsApp can share what they learned with their buddies.

Ultimately, Rabiah noted that Teach For Pakistan is still learning as an organization how to deal with this new and unprecedented situation. “We feel like there's an urgency for us to act right now so that our students feel like they haven’t lost the connection that they have with us,” she explained. “While the challenges might look different, the battle we are fighting is still against inequity and we can’t let our students lag behind while their privileged counterparts can move on.”